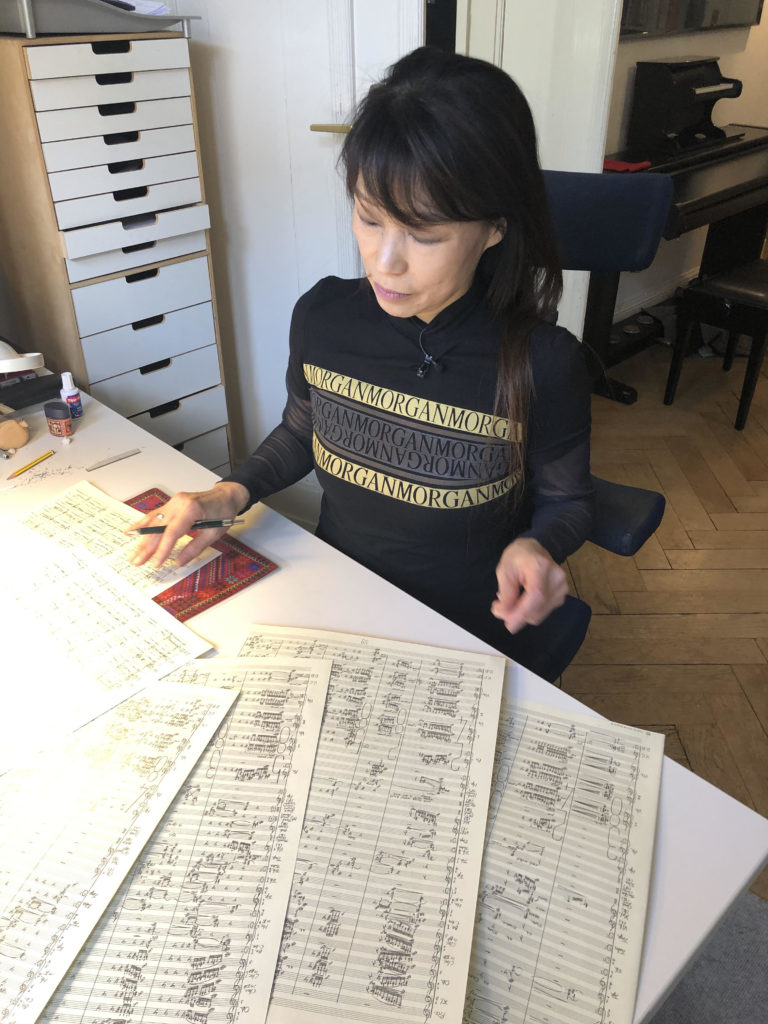

Unsuk Chin was artist in residence in Bergen International Festival 2019. Anders Beyer met the composer in her home in Berlin.

By Anders Beyer

Anders Beyer: Could you take us through your journey from your first meeting with music to where you are today as a celebrated, award-winning composer?

Unsuk Chin: I can’t say that I found music, music was always with me, even when I was a child. Around the age of two or three, I discovered the piano, and I immediately felt it was something I could live my life doing. So I started playing the piano and then wanted to become a pianist, but at the time my parents weren’t able to support me financially, so when I was 12 or 13 years old I decided to become a composer because, for me, it was a wider perspective.

AB: You were self-taught as a pianist?

UC: We had a piano at home and at the church where my father worked, but it was not possible to receive regular lessons. In Korea, we were in a difficult economic situation in the ’60s and ’70s. My sister was a singer and was five years older than me, and she had some books about counterpoint and harmony. I accompanied her a lot, and I learned a little bit with these books, and from the library, I brought lots of scores by Tchaikovsky, Brahms and Beethoven, and so I learnt to read scores and played many, many pieces on the piano. I discovered Beethoven and Mozart at a very early age.

AB: Going from the decision to be a performer, a pianist, to that of being a composer is a very tough move and was not natural for a woman at the time. It must have required some strength to say ‘this is my way’?

UC: You know, becoming a pianist was my big dream, my only passion in life, but we had no money for piano lessons. One day when I was 13 years old, my music teacher in school, who was himself a composer, called me, and he said, ‘maybe you could try to become a composer?’ To me, it sounded like ‘you can’t become a pianist’, so I was crying a lot. In those days there was a big event when Myung-whun Chung was a young pianist. He won a prize at a Tchaikovsky competition and became a national hero, and when he came back to Korea, there was a huge car parade in the street, and he was all over the newspapers. For about two weeks there were only articles about him and his sisters and his family, and it was everybody’s dream to become like him, and I thought maybe, for me, it’s too late anyway, so the decision to change my direction was very tough and sad at the beginning.

AB: How long did it take before you met famous composer Sukhi Kang who started teaching you and made you think, okay, maybe it’s not the piano but composing that’s right for me?

UC: After the decision, I learnt counterpoint and harmony and listened to lots of music, but I couldn’t get any regular lessons in composition. After six or seven years, I did the entrance examination at the Seoul National University to study Musicology, and I failed because I had no idea how the examination would be. The second year, I failed again. It was a totally tough time in my life because at a certain age everybody is doing their examinations and it’s all ‘are you successful or are you not’, and if you failed it was really tough. So then I did the examination at another university and was successful, but I didn’t want to stay there, I wanted to go back to Seoul and the National University. I prepared the examination once again, and the third time, I was successful because there were not enough applicants (she laughs). I was really lucky a couple of times in my early life, and if not, my life would be completely different now.

AB: You also say that you learnt from your failures and that despite your failures, you were strong enough to say ‘no, I want to do this’.

UC: Yes. I think my early life, maybe until I was 13, was very tough psychologically, including the study time with Ligeti. But it was very good mental training so nowadays I’m quite tough, and if I see any tough critique about my music or things like that it doesn’t touch me, I’m very strong.

AB: But you also have good critiques?

UC: Yes, but normally, I don’t read much critiques.

AB: When you studied with Sukhi Kang at university, did he at a certain point encourage you to travel to Europe?

UC: I think he encouraged me a lot because I was his first student when he came to Korea and became a professor, and he was extremely ambitious. He opened a door for me. Before I came to him, I wanted to go abroad and study in Germany or France or America, but it was just a dream. But he encouraged me very much, and he taught me that this dream could become a reality. He didn’t only open doors in terms of competitions, but also regarding contacts and all the other information. So, after my studies with him, I received a DAAD scholarship from the German government, so I was able to come to Germany.

AB: To Hamburg?

UC: Hamburg was the first city because I was allowed to study with György Ligeti.

AB: Ligeti was in a way in opposition to the avant-garde of the Darmstadt, but he was also in opposition to the American minimalism and kind of trying to find his own path. He didn’t actually compose for some years because he was in a crisis after the Horn trio. Can you tell us a little bit about his influence on you?

UC: I came to Ligeti in 1985, and he was in a period where he denied all his old avant-garde pieces. He was in different ways trying to find his own way. Of course, I had studied some avant-garde with Sukhi Kang. in Korea and had already written a couple of pieces, but Ligeti criticised them very harshly. I couldn’t understand this because, for me, contemporary music had to be like this. I was very naïve, and those three years with him were very tough, and sometimes I didn’t go to the lessons because it was mentally difficult to withstand it all. He was very intellectual, and he was always, always talking, and it was difficult to understand what he meant. But he opened another door for me into a much higher sphere, and maybe without this experience, I would compose completely different music, I don’t know.

AB: Did he say that your music was too academic?

UC: No, that it was a cliché, everyone did this kind of music with a very complicated score and lots of special effects. He told me my music could be something completely different, so I had to find it.

AB: He also worked with instrumental theatre in the works Nouvelles Aventures and Aventures and further on also in the opera Le Grand macabre, and I see that you also have this theatrical element in your music. Is that something that was inspired by him or did you find this along the way?

UC: I think both. I was inspired by all his works, but my affinity for music theatre comes from Korea. In everyday life, we had a lot of street theatres and also traditional drama, so I think it comes from both sides.

AB: And so, to a little bit about literature and theatre. You have a certain affinity to Samuel Beckett and to Alice in Wonderland. What attracted you to Beckett?

UC: Generally, I’m interested in surreal theatre because for me, it’s very musical. If I read surreal stories or theatre plays, I immediately imagine the music and sound, so maybe that’s why.

AB: You have stated that your music does not belong to any specific culture and that you always felt like a cosmopolitan. What effect has this had on your music?

UC: I think I said that when I was asked ‘You are Korean, why don’t you write Korean music or something more of your own tradition?’. I am of course a Korean, but I feel like a cosmopolitan, and the things which interest me go beyond nationality.

AB: Let’s talk cosmopolitan. You are inspired by gamelan music and Ligeti was also inspired by the rhythmical structures of African music. Tell us about this influence from various parts of the world.

UC: I think as a composer, I get lots of influence from different kinds of music, cultures and traditions, so for me, there are many genres, there are no borders. I like all kinds of good music. As a child, I was interested in classical music of course, but also in pop music, jazz and traditional music, all kinds, street music too. For me, there is no esthetical dogma.

AB: But your music will never be accused of being pop music, I think.

UC: No. I always try to learn what the core of the music is, so you know the style. The genre is just the clause, and it’s the core of the music that is most important to find and to judge.

AB: When I talk to musicians that play your music, they say that even if they are the best in the world, it’s very difficult and demanding but also very rewarding. You really challenge them?

UC: Yes, until now I have had lots of wonderful and bad performances and lots of different qualities, but for me it’s important that if the musician can play, if they are good musicians, they can play anything. For me, if they stay within their capability and play a piece good but in a very lazy, comfortable way, it doesn’t touch me. So I always want to drive good musicians to their limit, so they are always trying to survive. It’s like cooking, it’s a very small pinch of garlic or pepper or something that is very, very important.

AB: You like to play with words, and your literature and composition style has been called ‘playful’, and ‘full of surprises’. What role does humour and other sources of inspiration play in your work?

UC: Humour is very important because I like people with humour, it means the person is able to keep a distance from himself, so it’s a very, very important quality of personality for me. And not only humour but a certain sarcasm and also absurdism and all these kinds of characteristics I can create music with. I like it.

Photo: Thor Brødreskift.

AB: Let’s talk about the music we will hear in Bergen, should we start with the Piano Concerto?

UC: Yes, for me, the Piano Concerto is one of my most important works because it was my first big commission. I was in my mid-thirties, and nobody knew me as a composer. It was a very different period but very good for me because I thought a lot, and I spent a lot of time listening to music and was incognito. This piece was really hard work, I worked on it for more than six months and had big health problems because it was so stressful, but it was very important because at the time nobody knew me and I just didn’t think of what people would think about it. I just concentrated on the music, and that was nice. Now I’ve been a professional composer for more than 20 years, and you know, you lose things that you had as a young, unknown composer.

AB: So, do you look back with a little nostalgia? Do you look at them, the compositions at the time, like small children that you have left?

UC: No, but in this piece, there is a certain naïvity but also lots of freshness, and that’s what I like about it.

AB: Tell us a little about the work that is described as your career breakthrough, the Akrostichon-Wortspiel.

UC: I don’t think there is any breakthrough piece. For every piece and every performance, you think ‘yes, good critiques and good performances, people are paying attention, this is breaking through!’ But after a while, it was not, and the next piece would be the same, and it’s been like that for 30 years. Every piece is unique and important to me because there are many things in one that are not in others. So, for me, life as a composer is a collection of these breakthrough pieces.

AB: Some words on this piece Akrostichon-Wortspiel specifically?

UC: It’s an old piece but it was performed in London, so it was how I came to Boosey & Hawkes. It was like a fairytale story, so in that sense, you could say it’s a breakthrough piece.

AB: What is it about the piece?

UC: It was the first piece I wrote when I moved to Berlin after three years of dilemma and not writing anything while studying with Ligeti. It was my first instrumental piece after a long break, and it was on commission from the Gaudeamus Foundation, which was a commission for prize winners from the 80s. There was no money, just the performance, and it was really very tough work. The piece was not finished when I performed it. There were five movements, but during rehearsal, there were some problems and just five or ten minutes before the performance, I decided not to play the last movement. But people found it very good.

Then, after two years, I had the feeling one day that I had to finish this work, and without any commission or any plan for performance, I sat down and started to compose and completed all seven movements. The next day I got a letter from London from a certain Mr. George Benjamin, an English composer and conductor, that he would like to conduct my piece, and I answered ‘wonderful, I just completed the piece, you can premiere it!’. I thought he would be an old, white-haired English gentleman, but he was the same age as me. The opportunity to meet him and perform this piece in London was very important because even now, he is one of my best friends, we communicate often, and of course, I admire his music and his personality as a human being and also as a composer. After the performance, I got really good reviews in four important English newspapers.

After six months I got a call from somebody from Boosey & Hawkes who said, ‘someone sent us your piece’, and they gave me a contract, and I went from being proud just to even own a score by Boosey & Hawkes to suddenly being a composer with them. It was a big fairytale. Nobody wanted to tell me who had sent them the piece, so I wrote to George and asked if it was him, and he said yes. So it’s a very sweet story.

AB: You also worked closely with another conductor, Kent Nagano.

UC: Yes, and also Simon Rattle and a couple of other conductors. I think even though the beginning of my life was quite tough I always met the right person at the right time, and Kent Nagano contacted me in 1998 or 1999 after hearing my name from George Benjamin because they knew the composer Olivier Messiaen and Kent wanted me to write a piece for the Bayerische Staatsoper Orchestra. But the piece had to be finished within six months, and so I said no, I was a young unknown composer and it wasn’t possible to deliver a good piece that soon. He called again, and for 20 minutes, he tried to persuade me to say yes, but I said no again. And that was my first contact with Kent Nagano.

AB: But did he persuade you in the end?

UC: No, he thought it was impossible to persuade me and accepted my decision, and then he gave me another commission for a later time. Our contact still remains, it is a very rare and special musical relationship. He has performed a couple of very important pieces of mine and has helped me a lot in my career as a composer.

AB: Another piece we will see in Bergen is Cosmigimmicks, which is maybe not a comic piece. Could you tell us a little about it?

UC: The idea for Cosmigimmicks came in 2004 and 2005. I have a very good musical relationship with Nieuw Ensemble in Amsterdam, my piece Akrostichon-Wortspiel was premiered by them. I was sitting with the artistic director Joël Bons, also a wonderful composer, and suddenly I had an idea just for this ensemble. Their instrumentation is very special, they have three plucked string instruments, the guitar, the mandolin and the harp, and I told them one day I will write a piece for seven musicians. So, seven or eight years later – they had to wait a long time – I composed a piece. I wanted to write a piece with visual imagination, so I decided to divide the whole piece in three, and then each movement has its own theme and can be danced or visualised, and it has a certain abstract, surreal character.

AB: Then we have your string quartet which reminds me of the whole electronic side of your output, could you tell us about what we will hear?

UC: The string quartet ParaMetaString was commissioned by Kronos Quartet, and the kind of music they play is quite different from my music.

For me, a string quartet is a very traditional form, so it was very difficult to have an idea for one. But the Kronos Quartet wanted me to write a piece and at that time I was still a young and unknown composer and you don’t say no, so I wanted to do this piece and was in a dilemma of how to solve this problem because there are lots of contemporary string quartets with lots of special effects and all this kind of cliché. It seemed to be impossible for me to write an interesting string quartet, so I decided to start a string sound with an electronic experiment. I recorded some samples and experimented for six months in a studio without any specific ideas and found very interesting things, so I thought okay, I can take an element of a piece and then build up the whole piece so it’s four different movements with four different effects and ideas.

AB: And you are controlling the electronics yourself?

UC: At that time, yes, it is just a tape as I don’t like live electronics. If you do tapes you can have perfect control and the string players will also be amplified and they will play to the click track. It is really quite tough for the musicians, they have to be synchronised to the tape.

AB: What are your thoughts on being the 2019 festival composer in Bergen? Do you think music festivals add to the cultural canon? Tell us a little bit about your expectations and what you think about it.

UC: You know, it may seem like as a Korean in Norway we wouldn’t have anything in common, but one of my biggest events as a composer was in Oslo in 1990 at the ISCM World Music Days. My piece Troyan Women was first performed there at the opening, and the then Crown Prince Harald was also there, so for me, it was a very important occasion. I also have a very good musical relationship to Stavanger, I was invited as a composer in residence in the Stavanger Symphonic Orchestra, and I was really surprised by how high the quality of the musicians was. Troyan Women was also performed by the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, and I was in Bergen for one week for the rehearsals for that concert, and it was the first time I was in Norway. The landscape is so beautiful, and the people were so nice, and the orchestra was incredibly good. It was really an unforgettable memory for me, and now I’m coming back to Bergen, it is really a touching experience which I’m really, greatly looking forward to.

AB: Oh, thank you so much. That 90’s experience was also a turning point in the contemporary music life of Norway because at the ISCM World Music Days we also saw the opening of the Ultima Festival. So you have always been in the right place at the right moment. We are looking forward to seeing you in Bergen in May and looking forward to your music.

© Anders Beyer 2019

For a Norwegian version please click here

A short version of the interview was published in Norwegian in ballade.no:

https://www.ballade.no/kunstmusikk/festspillkomponist-unsuk-chin-inn-til-kjernen/

See video portrait of Unsuk Chin by Anders Beyer, filmed in the composer’s home in Berlin March 8 2019. Photographer: Anita Vedø.

Video: Smau Media